“I fear the loss of those I love more than my own death.”

My father would arrange the flowers on the family graves by the Sunday before Memorial Day. Being a native Ozarker, he was familiar with the holiday’s previous name and would have referred to the flowers as “decorations.” Even though the family members whose bones were protected by these grassy plots had passed away years or even decades before, their remembrance endured.

During these yearly rites, as a child and unwilling participant, all I could do was locate a nearby tree’s shade and pay attention to the person reciting the names on the stones with the bored indifference of a designated witness. I had only really known my grandmothers, maybe one or two of them for example — but the rest were as distant to me as the sun overhead.

Memorial Day was the one occasion my father observed with the strictness of a civil religion, even though he was not a particularly religious or ceremonial person. For Carl McCoy, Memorial Day marked the start of the year rather than the longer days following the winter solstice. The somber commemoration of the deceased usually came to an end with a family dinner (very seldom a picnic), after which the doors were thrown wide to summer and its long days, baitcaster fishing, and, by July Fourth, homegrown tomatoes.

He was almost fanatical in his preparations for Decoration Day. Maybe it was because he himself had been a sailor aboard the battleship Pennsylvania during World War II, or because the majority of the males in our extended family had served in the armed forces. Or it might have just been a chance to honor all of the departed family members, soldiers included, without having to enter a church or recite a prayer. He was a gifted salesman with good communication skills, but he was reserved when it came to expressing his emotions and uneasy with socially acceptable acts of religiosity or patriotism.

He would honor the dead in his own way.

First, there was the issue of the decorating container.

Growing up during the Great Depression, he followed the most important advice given to everybody who has gone through hardship: do not waste anything. Thus, pots and vases from the store would not work. Rather, he used to save his empty one-pound coffee tins for a year before spray-painting them blue or red. The flowers didn’t come from stores either; instead, they were from his yard or, with permission, from friends’ and neighbors’ gardens.

He didn’t seem to have a favorite kind, but asters, hydrangeas, and peonies were all present. For the trip to the graves, a small amount of water was filled each can from the tap, the cut flowers were inserted, if not organized, and then the cardboard pallets were placed in the trunk of his bronze-colored Thunderbird (after, a blue Buick that I never really liked). He lived the majority of his life in Joplin, Missouri, where both of them were raised.

He would begin in the southwest at Osborne Memorial Cemetery and finish in the northeast at Forest Park. Osborne is a vast area of hills covered with grass and trees that was created in the 1930s by the Works Progress Administration. It is divided from an outside road by native stone wall.

There are people from both Kansas and Missouri buried there, including grandparents, cousins, aunts, and uncles, as well as members of both sides of my family. The majority of the men’s graves had flags on them, signifying that they were veterans. Speaking as he went from one graveyard to the next, my father would make comments about this or that person’s past while holding his tin-can decorations. My mother would be buried there in 1986, having passed away from cancer, but at that point my parents had already split up, so he didn’t say much about her burial. Still, one of those painted cans was placed on her grave.

Throughout her life, my mother endured immense torment, and in the final weeks before her death, she experienced existential agony that could only be alleviated by a drip of morphine. Finally, she slipped away, and it seemed like a kindness. Although breast cancer proved to be the ultimate cause of her suffering, the other elements are still a mystery that she herself only knows about. This enigma is made worse by the fact that she had obviously suffered from depression for the majority of her 59 years.

Death seemed as abstract to me as quantum mechanics when I was a child. The dates on the headstones were unreal, and the majority of the names were cyphers. That was altered by my mother’s passing. At the age of 28, death ceased to be an abstract concept and instead represented the conclusion of a story: one lives, one dies, either quietly or terribly, and the tale is over. I was incensed by my mother’s story since it sounded like she made the decision. I was so furious that, in an attempt to make sense of her story, I would murder off characters that represented her in my stories.

Years would pass before I understood that lives, particularly hers, were more complex than either sad or joyful endings. Joy and grief come to everyone of us in due time.

Unplanned family get-togethers occurred frequently at Osborne. Relatives who lived hours or even days away in other cities and whom we hadn’t seen in a year or three would park their cars and arrive carrying decorations. Naturally, a lot of the conversation at the cemetery revolved around the past, occasionally tinged with sorrow and animosity. My dad remembered going barefoot throughout the nearby hillsides and carrying just a few shells for his.22 rifle to catch and cook squirrels. Occasionally, he would recount how his sister had hidden a Hershey bar and eaten it late at night. Despite the fact that they were both young and his sister was two years younger than him, my father saw his sister’s refusal to share as a betrayal he carried with him for life.

The people I visited at the other cemetery, Forest Park, were all buried in the old portion on the north, and on my father’s side. Unlike Osborne, this place was semi-wooded and had graves dating at least as far back as the 1870s. When my grandfather and other family members’ graves were overgrown with weeds and vines, my father would always bring clippers and other tools to trim them back. However, he would never remove the wild strawberries from Sgt. William J. Leffew’s grave, a former Confederate and Tennessee cavalryman who had been a family friend in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Since all of the men in my father’s family were veterans of the Union, I’ve often wondered how it came about.

During the summer of 1997, my father had already moved into one of the hills at Osborne and had a small American flag flown over his tomb on Memorial Day.

The aneurysm had occurred quickly, initially manifesting as an almost blinding headache; but, upon regained consciousness, he instructed his neighbors to contact me. He was unconscious and the doctors stated there wasn’t much they could do when I got to the hospital, which was a little over an hour later. Death was inevitable. I felt his toes as his bare feet protruded from under the covers at the end of the hospital bed and was struck by how young they appeared for a seventy-three-year-old guy.

I no longer found death to be so abstract. It also felt like a continuation of the story rather than the conclusion of one. However, I was unsure if the story held any significance or was only a matter of cold facts: people are born, people die, and if your life path coincides with that of the departed, you would probably experience sadness.

Later on in my life, I formed an unanticipated friendship.

Phil was a free thinker, a fellow writer and journalist, and occasionally a pain in the ass, but he was always an advocate. We felt like we had known each other for our whole lives since we had so many things in common, including reading, photography, science, philosophy, and scuba diving. I was in love with my, he told me wife, Kim, before I knew it myself, and he bought the champagne for our wedding.

I had Phil as my best friend for five years. I wrote about him previously, as you may recall, in this Kansas Reflector article from 2021.

Due to a stomachache, Phil withdrew from a writing conference with me in the fall of 2011. He expressed his confidence that it was just a little case of the stomach flu. But in three months he would pass away from colon cancer.

He never moaned as the end drew closer, and he even managed to crack jokes about his impending death. He was only able to consume a few bites of the food that Kim and I provided him. He didn’t feel down, he accepted his impending death, and he didn’t believe in any form of hereafter. I had an overwhelming urge to stay with him at the end, to hold his body close to mine as he grew weaker and the days got shorter. The coming death of Phil was tangible, visceral, the unwavering stone of reality—far from being abstract or a plot point. Not just to him but to everyone who loved him, especially his kids, it was blatantly unfair. He was ultimately carried away by a sister.and passed away in Colorado’s Rockies. Kim and I experienced waves of ever-deepening anguish when he passed away. Even if the swells have decreased, they continue to occur 12 years later.

A simple reading is that I was grieving my own mortality. Perhaps. But there was more to the pain, I think. My reaction was an existential cry to the inevitable loss of all we hold dear to time and random misfortune. That we must die is certain. To really live, and not just survive, is the challenge. My grief was deep at Phil’s death precisely because he had lived so deeply and in so doing had touched my life and that of many others.

A deeper experience was had not too long ago when my brother passed away. Like my father, he had served in the military and was many years my senior. He lived a full life before suffering a heart attack at home, which was a typical way to die. My brother’s death was like a stone under my ribs if Phil’s was like a stone hitting a rock.

My fear is not of dying, but of losing the people I care about.

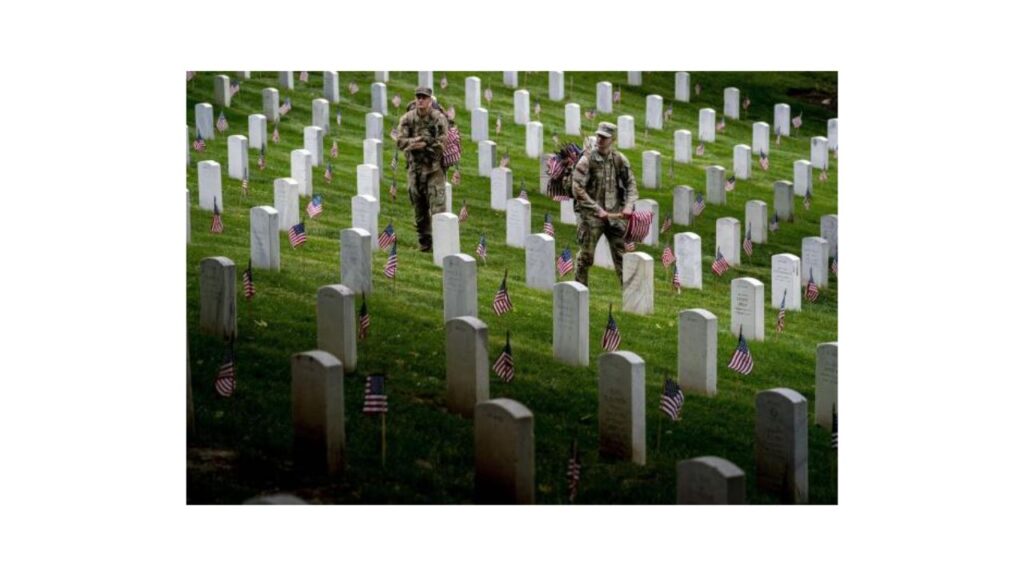

Monday will bring an end to a long weekend dedicated to remembering our war dead. As a national day of memorial for the men and women who have lost their lives serving their country in all battles, the Civil War tradition is still observed today. To honor them, we don’t have to impose a heroic story on them or pass judgment on the battles they lost. Tennyson’s “Charge of the Light Brigade,” which honors the bravery of Crimean military soldiers who were killed due to an administrative “blunder,” comes to mind. It’s arguably the most well-known military poetry ever composed.

The Civil War, which claimed the lives of over 600,000 men, was a horrific event that altered the way Americans perceived death. Because of this, embalming became widespread, beginning with Col. Elmer Ellsworth, the first-ever Union officer to die in combat. After he cut down a rebel flag from a rooftop in Alexandria, Virginia, in May 1861, he was shot and killed. Being a close friend of Abraham Lincoln, he had attempted to have the flag taken down because it could be seen from the White House. After being embalmed, Ellsworth’s body was transported to New York, where it was seen by hundreds of people, and it laid in state at the White House for many days.

Local remembrances of the fallen soldiers spread throughout the north and south after the war, quickly becoming annual springtime observances. Memorial Day was commemorated on May 30 from 1868 to 1970. In 1971, it was declared a federal holiday and fell on the final Monday of May.

Even though the Civil War helped to develop current burial customs, its terrible aftermath—nearly every family suffered a death—saw a rise in spiritualism as mediums claimed to be in contact with the dead.

If there is an afterlife, I’m not sure. Shakespeare’s “secret house of death” is yet unfathomable. Either the riddle will be solved after we die, or it will remain buried deep in the past. Our monuments and cemeteries are more like stone question marks than they are glorified relics.

From these inquiries, a collective story of selflessness in the service of justice has surfaced. Joseph Campbell defined a hero as “someone who has given his or her life to something bigger than oneself,” and I agree with this definition, even though I believe the term is used too loosely these days.

This Memorial Day weekend, remember the deceased with reverence. But set aside some time to honor the living. Take part in other people’s happiness and grief. Have the courage to love despite the possibility of breaking your heart. Consider the things that are greater than you. And even if it’s only a painted coffee can full of borrowed flowers, make an act of civic prayer to the strength and wonder of our collective national memory.