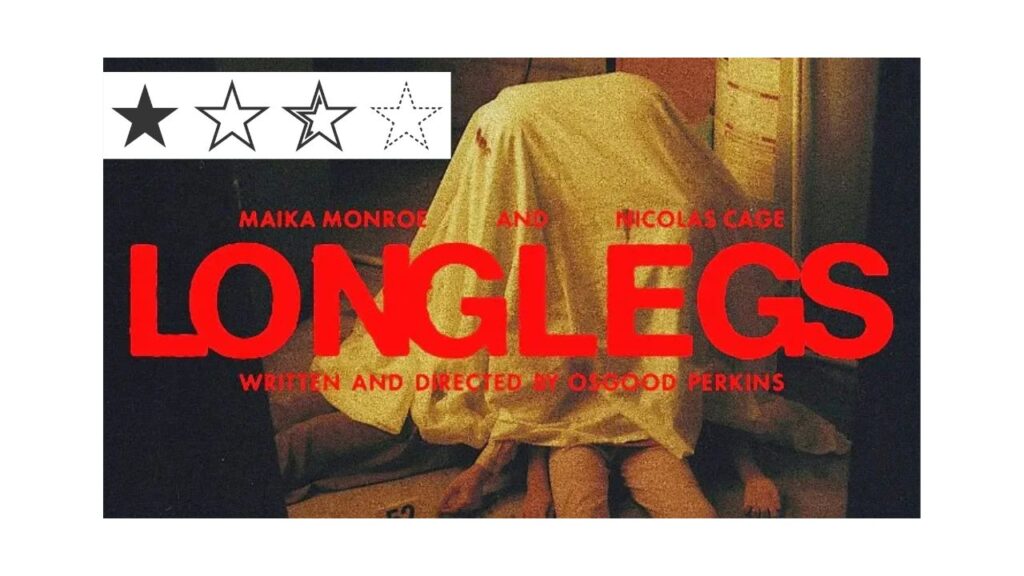

Review: Maika Monroe is razor-sharp in the suspenseful thriller “Longlegs.”

“Longlegs,” a masterfully composed horror film from Osgood Perkins set in the 1990s about a rookie FBI agent whose history appears to hold the solution to a decades-long suburban serial murderer spree, has an eerie, half-remembered encounter hanging over it.

The first flashback scene in “Longlegs” features a little girl meeting a stranger in her snow-covered yard after leaving her home. His face is never shown to us above the bottom half, yet even then, there’s an overpowering feeling of creepiness. The video abruptly ends before “Longlegs” even starts, accompanied by a scream.

That girl is now grown and included in the investigation, which took place 25 years ago. Although she is exceptionally skilled at figuring out the serial killer’s carefully planned targets, she has a blind spot in terms of psychological awareness. The most eerie mystery in Osgood’s suspenseful, albeit clichéd, horror film about an elusive boogeyman is the hazy, broken quality of childhood recollection.

“Longlegs,” which hits theaters on Thursday, is bringing a lot of mystery with it, as seen by a protracted and intriguing marketing campaign. Is all the hype justified? That may depend on how much you can take from a very serious procedural that masterfully builds suspense and then descends into a jumble of horror clichés, including creepy dolls, satanic worship, and an absurd Nicolas Cage.

It is a testament to both Monroe and the terrifyingly captivating first part of “Longlegs” that the third section of the movie falls flat. The prologue is followed by a wider screen. It is displayed in a boxy ratio with rounded corners, as if viewed from an overhead projector. Harker is a gruff, reclusive detective assigned to a big task team to find the criminal responsible for the deaths of ten families over a thirty-year period. Sent to knock on doors, she looks up at a window on the second floor and knows right away. She warns a partner, whose lack of trust in her instincts turns out to be disastrous, “It’s that one.”

When Harker is brought in for a psychological assessment, her odd clairvoyance is revealed. Agent Carter provides her with all the gathered evidence, which at the moment indicates to no intruder into the homes of the dead but suggests the same culprit (every crime scene has a coded note left signed by Longlegs). It makes Carter think of Charles Manson. Harker reminds him that Manson had accomplices. Of further concern is the fact that every victim had a daughter whose birthday falls on the 14th of the month—a characteristic that Harker inevitably shares.

Families also play a significant role in the story. Harker pays her mother a visit every now and then, and their brief exchanges reveal that she is aware of the cruelty in the world. Harker informs her over the phone that she’s been preoccupied with “work stuff” one time.

“Yucky stuff?” the mother queries. Yes, she responds.

As they pursue the murderer through rural Oregon, terrifying scenes are seen. They visit the same locations on a regular basis: abandoned murder scenes, closed barns, and former inmates of mental health facilities. In addition, Longlegs is skulking around and leaves Harker a letter. He appears to us briefly at first. The closer we go to this bleached, pale man with long white hair, the more clownlike he appears. If Manson was a product of the 1960s, Longlegs seems more like a creation of the 1970s, especially with his white Bob Dylan Rolling Thunder Revue visage. The Lou Reed album cover for “Transformer” is positioned above T.Rex’s mirror, and he opens and shuts the movie.

Perkins is the film-making son of Anthony Perkins, who gained notoriety for portraying one of the creepiest villains in a movie, Norman Bates in “Psycho.” Perkins has stated that the film “Longlegs,” which he also authored, has personal roots because of his own background and his father’s complex personal life. However, a deeper force is trying to get through “Longlegs.” It appears that nothing but other movies is the primary source of its sensation of fear. There are two definite touchstones: “Se7en” and “The Silence of the Lambs.” In the end, Longlegs seems more like Cage’s big-screen vehicle and stock boogeyman.

Either way, this is a Monroe film. Her captivating on-screen persona in films such as “It Follows” and “Watcher” has made her the leading “Scream Queen” of today. She is talented in more than one genre, though. In “Longlegs,” Monroe’s Harker encounters a particularly unsettling situation repeatedly and enters straight away. It’s not that she’s not anxious; in fact, Eugenio Battaglia’s masterful sound design incorporates her labored breathing. Steely and powerful, Monroe slices through this almost cartoonishly harsh movie like a knife. icky material? Yes.

The Motion Picture Association has rated Neon’s “Longlegs” R due to graphic violence, unsettling imagery, and occasional language. 101 minutes of running time. An overall rating of 2.5 stars out of 4.