He transformed from an M.I.T. professor to a multibillionaire by using cutting-edge computers. For decades, the average yearly return on his Medallion fund was 66 percent.

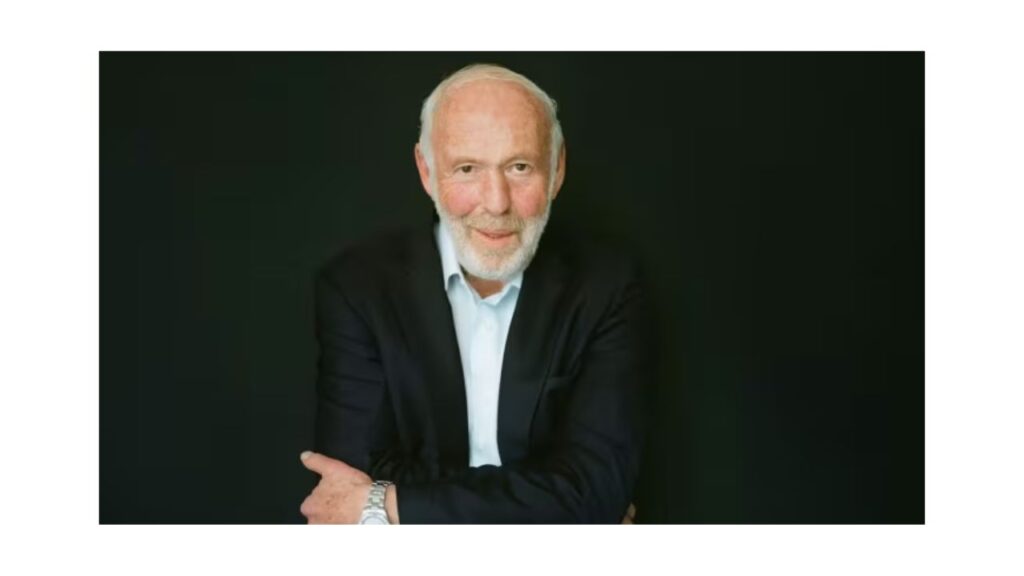

Jim Simons, the mathematician who won a prize, gave up on a brilliant academic career, and entered the world of finance, about which he knew nothing, to become one of the most successful Wall Street investors ever, passed away at his Manhattan home on Friday. He was eighty-six.

Jonathan Gasthalter, his spokesperson, confirmed his passing but did not provide an explanation.

Mr. Simons turned his mathematical prowess toward a more mundane endeavor after releasing ground-breaking research that would eventually become fundamental to the fields of condensed matter physics, string theory, and quantum field theory.

Therefore, he decided to prove that trading stocks, bonds, currencies, and commodities could be almost as predictable as mathematics and partial differential equations when he opened a storefront office in a Long Island strip mall at the age of 40. He recruited scientists and mathematicians who shared his views, turning down financial analysts and recent business school grads.

In order to handle massive amounts of data sifted by mathematical models, Mr. Simons provided his colleagues with cutting-edge computers. He also transformed the four investment funds in his new company, Renaissance Technologies, into virtual money making machines.

The biggest of these funds, Medallion, made almost $100 billion in trading gains in the three decades that followed its establishment in 1988. During that time, it produced an unprecedented average annual return of 66 percent.

That was a considerably superior long-term return than experienced investors such as George Soros and Warren Buffett were able to accomplish.

Gregory Zuckerman, one of the few reporters to interview Mr. Simons and the author of his biography, “The Man Who Solved the Market,” stated, “No one in the investment world even comes close.”

By 2020, about a third of Wall Street trading activities were driven by Mr. Simons’s method of investing in the market, known as quantitative, or quant, investing. Even conventional investment businesses, which depended on intuition, personal connections, and company research, were forced to embrace parts of Mr. Simons’ computer-driven approach.

Renaissance funds were the biggest quant funds on Wall Street for a significant portion of its history, and their trading and profit-making strategies revolutionized the way hedge funds catered to their affluent clients and pension funds.

Ten years later, Mr. Simons’s fortune had doubled. He was worth $11 billion (almost $16 billion in today’s currency) when he stepped down as the company’s chief executive in 2010.

As chairman of Renaissance, Mr. Simons continued to manage his money, but he also spent more and more of his time and resources on charitable endeavors. One of the biggest private sponsors of basic science research is now the Simons Foundation. Additionally, his Flatiron Institute conducted research in quantum physics, astrophysics, biology, mathematics, and neuroscience using state-of-the-art computer methods.

James Harris Simons, the sole child of shoe factory general manager Matthew Simons and house manager Marcia (Kantor) Simons, was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on April 25, 1938. An extraordinary mathematician, he completed his undergraduate studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and, at the age of 23, graduated from the University of California, Berkeley with a doctorate.

Mr. Simons began teaching at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University in 1964. He also worked as a Soviet code breaker for the publicly sponsored nonprofit Institute for Defense Analyses. However, in 1968, he lost his job at the institute after openly voicing his vehement opposition to the Vietnam War.

He became the math department chairman at Stony Brook University, a branch of the State University of New York, where he taught mathematics for the following ten years. In 1975, while serving as the department head, he was awarded the top geometry prize in the country.

Afterwards, in 1978, he gave up his academic career to start Monemetrics, an investment firm located in a small mall in Setauket, on Long Island’s North Shore, just east of Stony Brook. He had never enrolled in a course on finance or demonstrated anything more than a casual interest in the markets. However, he was confident that he and his tiny group of statisticians, physicists, and mathematicians—most of whom were former colleagues from universities—could evaluate financial data, spot market trends, and execute successful trades.

Following four turbulent years, Monemetrics changed its name to Renaissance Technologies. At first, Mr. Simons and his expanding team of former academics concentrated on currencies and commodities. Renaissance was able to generate enormous annual returns by continuously utilizing a wide range of data sources, including news stories about political turmoil in Africa, bank figures from small Asian countries, and the rising price of potatoes in Peru. These data sources were fed into sophisticated computers.

The real gold mine, however, was discovered when Renaissance ventured into stocks, a far bigger market than commodities and currencies.

Long regarded as the domain of Wall Street brokerages, investment banks, and mutual fund companies, stocks and bonds were analyzed by youthful, industrious M.B.A.s who then forwarded their findings to senior wealth managers, who used their intuition and experience to identify market winners. At first, they mocked the Renaissance math geeks and their quantitative approaches.

Mr. Simon’s methodology resulted in some expensive errors. His company bought so many Maine potato futures with a computer program that it almost dominated the market. The regulatory body overseeing futures trading, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission, objected to this. Consequently, Mr. Simons lost out on a substantial possible return and was forced to sell off his investments.

More often than not, though, he was so effective that keeping his research and trade secrets secret from rivals was his hardest challenge. In a letter to clients, he stated, “With all due respect to the principles of free enterprise, visibility invites competition—the less the better.”

Not just competing businesses were envious or suspicious of Mr. Simons’s achievements. Outside investors revolted against him in 2009 due of the massive discrepancy in Renaissance Technologies portfolio performance. The Renaissance Institutional Equities Fund, which was made available to outside investors, saw a 16 percent decline in 2008 compared to the previous year’s 80 percent gain recorded by the Medallion Fund, which was exclusively open to current and former Renaissance workers.

When Mr. Simons and his company used financial derivatives to pass off daily trading as long-term capital gains, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations expressed bipartisan disapproval of them in July 2014. During his introductory remarks, Republican Senator from Arizona John McCain said that Renaissance Technologies had been able to evade paying almost $6 billion in taxes.

Mr. Simons and Robert Mercer, his former co-chief executive, were two of the biggest donors of money to political candidates and causes. Despite Mr. Simons’ typical support for liberal Democrats, Mr. Mercer has strong conservative beliefs and was a major contributor to Donald Trump’s presidential campaigns.

Since Mr. Mercer’s political actions were inciting other prominent Renaissance executives to consider resigning, Mr. Simons, the then-chairman of Renaissance Technologies, removed Mr. Mercer as chief executive officer in 2017. As a researcher, Mr. Mercer remained employed. Both men claimed that they stayed cordial and carried on with their socializing.

His organization awarded Stony Brook University $150 million in 2011, with the majority of the funds going toward medical sciences research. It was, at the time, the largest gift in SUNY’s history.

With a $500 million pledge to Stony Brook last year, the foundation surpassed that sum, which the university described as the greatest unrestricted endowment gift in American history.

As Mr. Simons became older and more prosperous, he lived an opulent lifestyle. He paid $100 million for a 220-foot boat, acquired a Manhattan Fifth Avenue penthouse, and possessed a 14-acre home with a view of Long Island Sound in East Setauket. He was a chain smoker who voluntarily paid fines rather than put out his cigarettes at meetings or offices.

His first marriage ended in divorce. Barbara Bluestein was a computer scientist, and the couple produced three children: Elizabeth, Nathaniel, and Paul. Following that, he wed economist Marilyn Hawrys, a doctoral student at Stony Brook who had previously attended as an undergraduate. Audrey and Nicholas were their two children.

In 1996, Paul Simons, 34, lost his life in a cycling accident, and in 2003, Nicholas Simons, 24, drowned off the coast of Bali, Indonesia. He is survived by his wife, other children, five grandsons, and one great-grandson.

According to his biographer, Mr. Simons expressed his sorrow about his sons’ deaths to a friend, stating, “My life is either aces or deuces.”